Change is a constant in our global environment, but that's all the more reason to keep moving forward on your terms.

Article

Australian service exports to China have been increasing for more than ten years. The Australia-China Trade Report highlights the trends in the services sector from 2009 – 2014.

Australian service exports to China have been increasing for more than ten years. Performance is strongest in areas where Australia has internationally recognised expertise or can bring its own unique comparative advantages to bear, for example in in-bound education and tourism.

In cross-border and in-country provision of services in China, Australian providers are subject to regulatory constraints and face the same hurdles as providers from other countries. When, in November 2013, China’s new leadership released their 60-point decisions as the economic blue-print for the period until 2020, they included three commitments to opening up services to international competition. The first was to treat domestic and foreign service providers on the same basis; the second to establish the China (Shanghai) Free Trade Zone and the third, and most detailed, was a list of service sectors to be opened.

To date, the opening up of the Chinese service sector has been gradual, with reform being rolled out cautiously via pilot projects and coordination with stakeholders. This makes the progress and sequencing of these reforms difficult to predict, but at the same time creates incentives for Australian business to be involved at an early stage such as the big Australian banks or AMP have done.

Australian companies have achieved partial breakthroughs in insurance, banking and currency trading. At the same time, Australian financial and professional service providers are opening up two-way business opportunities for their Australian and Chinese clients. Australian companies operating in a market environment are doing well in other service sectors such as architecture and design.

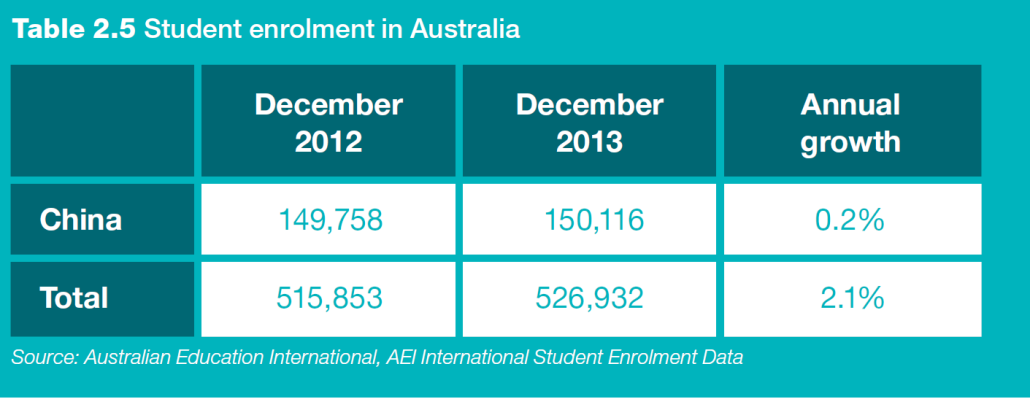

Turning to services provided to Chinese clients and consumers within Australia, education and tourism are the backbone of Australian-based service exports that produce huge community benefits. China is Australia’s biggest market for international students. As of December 2013, 28% of international students studying in Australia came from China (Table 2.5). Growth in student numbers from China has stabilised in recent years. Between December 2012 and December 2013, the annual growth rate was only 0.2%, lower than the overall growth rate for international student enrolment. Chinese sources indicate that demand for overseas education is stabilising and that flat growth for Australia is the trend, while the United States and United Kingdom are performing slightly above trend.

While numbers in the education sector are stabilising, the number of Chinese tourists travelling to Australia is growing strongly overall with seasonal fluctuations (Figure 2.6).

China is now Australia’s fastest growing inbound tourism market. Tourism Australia’s latest projections suggest that annual spending by Chinese visitors to Australia could rise to $13 billion by 2020, an increase of nearly 50 percent on the previous estimate of $9 billion in 2011.24 The potential for growth in in-bound tourism from China is illustrated by the family-owned Tangalooma Island Resort which receives 40,000 Chinese visitors a year. Tangalooma Island Resort built up a network of travel agents in China that enabled them to target more affluent customer groups and then match expectations with carefully selected services in the resort.

Australian service providers in China are making slow progress as they await regulatory change in service areas that are tied to reforms of China’s domestic services, some of which are state-controlled or under state monopolies.

Services open to market supply and demand offer better opportunities and are expected to grow, driven by China’s consumer and producer demand. For example, in the healthcare sector, Chinese companies such as Lancare Australia operate across both markets to combine health service provision in Australia and China.

For the Australian education sector, faced with stabilising Chinese student arrivals, the challenge is to generate higher added value by providing more differentiated products and improved or differentiated services, with an emphasis on high quality learning, work-integrated learning and strong graduate outcomes. Similarly, the future growth of the Australian tourism sector will depend on its ability to shift from organised travel tours to more high value-added free independent travellers.

NAB Sponsored 2014 Australia-China Trade Report Commissioned by The Australia China Business Council (ACBC). Page 34 – 35.

© National Australia Bank Limited. ABN 12 004 044 937 AFSL and Australian Credit Licence 230686.